James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper

Autograph Letter Signed Discussing Libel Lawsuit - 1839

An important autograph letter signed by American author James Fenimore Cooper in which the writer discusses a very public libel lawsuit he instigated against various newspaper editors who wrote unfavorable reviews of his work, including Horace Greeley, Park Benjamin, Elius Pellet, and Thurlow Weed.

Born in New Jersey in 1789, James Fenimore Cooper was the son of Judge William Cooper, the founder of Cooperstown, New York.

When Cooper set sail with his family for Europe in 1826, he was at the height of his reputation with critics and of popularity with his readers. His novels such as The Spy, The Pioneers, and The Last of the Mohicans were also selling so well that he could afford to travel and reside in Europe for the next several years. During that time, however, he published certain works that seemed to Americans to be unfairly critical of his homeland, so that when he arrived back in New York in 1833 he was already becoming regarded as an antidemocratic, pseudo-aristocratic scold.

After returning home, Cooper repurchased the family estate, including land on Lake Otsego called Three Mile Point, which his father had allowed villagers to use as a picnic site. On July 22, 1837, Cooper placed a notice in the local paper forbidding further public use of the Point. That curtly worded notice became the source of eight years of controversy and litigation.

Residents held a town meeting protesting Cooper’s actions and drew up resolutions to remove Cooper’s book from the local library. Elius Pellet, editor of the Chanango [NY] Telegraph chronicled the conflict that August. The article was republished in the Albany Evening Journal by Thurlow Weed, and in the Otsego Republican by Andrew Barber.

Cooper demanded a retraction from Barber, and in September 1838 he sued Pellet and Barber for libel, the subject of this letter. That suit, for replication of libelous materials, was the first to come to trial in the Fonda, New York, courthouse in May 1839, the month Cooper wrote the letter. The judge directed a verdict of $400 in favor of Cooper (about $10,000 adjusted for inflation), a judgment that was upheld on appeal. In March 1841, Cooper had authorities seize Barber’s press and types to settle the award, bankrupting the editor.

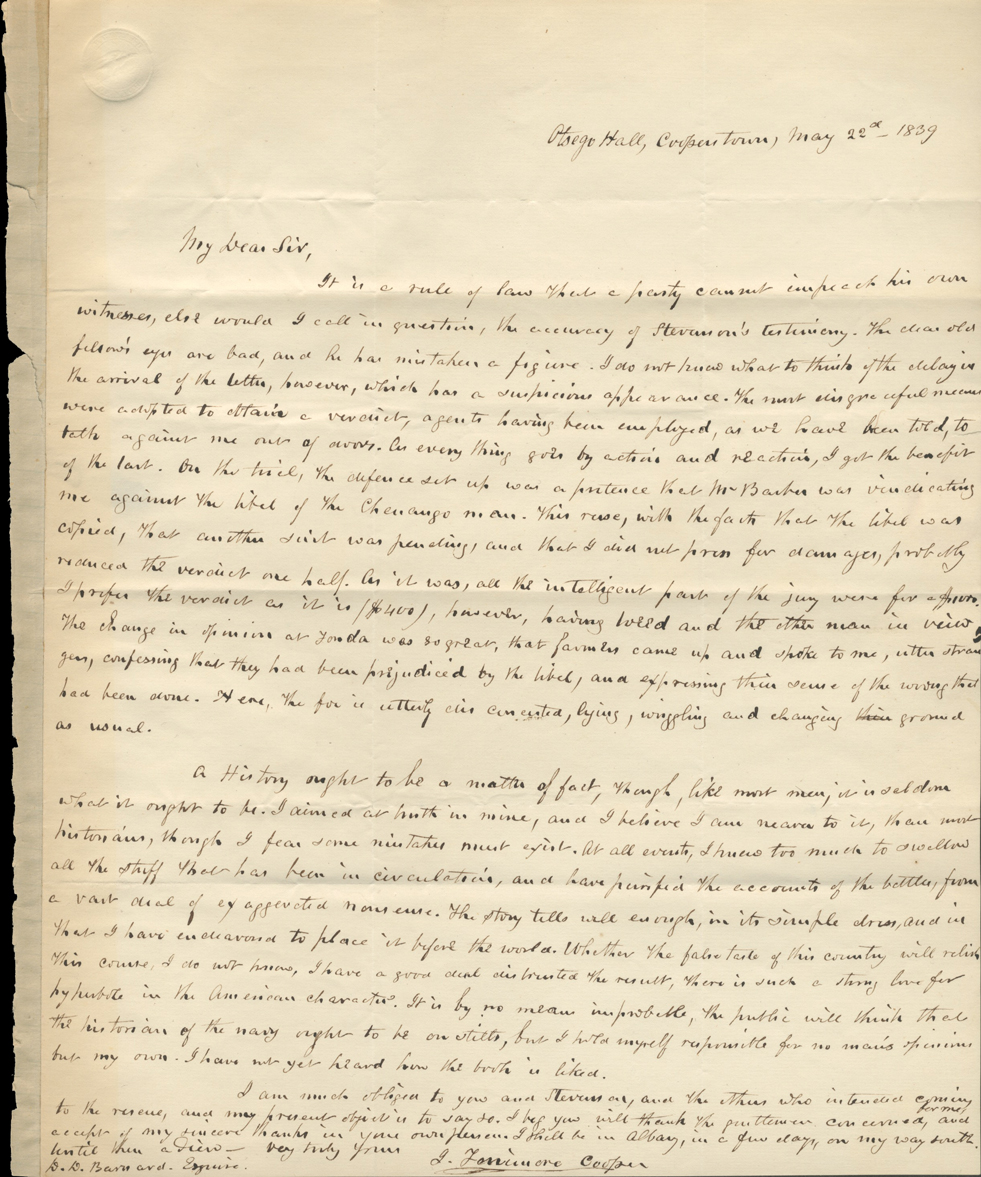

This letter, written to New York Congressman Daniel Dewey Barnard, reads:

Otsego Hall, Cooperstown, May 22nd, 1839

My Dear Sir,

It is a rule of law that a party cannot impeach his own witnesses, else would I call in question, the accuracy of Stevenson’s testimony. The dear old fellow’s eyes are bad, and he has mistaken a figure. I do not know what to think of the delay in the arrival of the letter, however, which has a suspicious appearance. The most disgraceful means were adopted to obtain a verdict, agents having been employed, as we have been told, to talk against me out of doors. As everything gets by action and reaction, I get the benefit of the last. On the trial, the defense set up was a pretense that Mr. Barber was vindicating me against the libel of the Chenango man. This ruse, with the fact that the libel was copied, that another suit was pending, and that I did not press for damages, probably reduced the verdict one half. As it was, all the intelligent part of the jury were for ____. I prefer the verdict as it is ($400), however, having Weed and the other man in view the change in opinion at Fonda [NY] was so great, that farmers came up and spoke to me, utter strangers, confessing that they have been prejudiced by the libel, and expressing their sense of the wrong that have been done. Here, the fox is utterly disconcerted, lying, wriggling and changing ground as usual.

A history ought to be a matter of fact, though, like most men, it is seldom what it ought to be. I aimed at truth in mine, and I believe I am nearer to it, than most historians, though I fear some mistakes must exist. At all events, I knew too much to swallow all the stuff that has been in circulation, and I have purified the accounts of the battles, from a vast deal of exaggerated nonsense. The story tells well enough, in its simple dress, and in that I have endeavored to place it before the world. Whether the false taste of this country will relish this course, I do not know, I have a good deal distrusted the result, there is such a strong love for hyperbole in the American character. It is by no means improbable, the public will think that the historian of the Navy ought to be on stilts, but I hold myself responsible for no man’s opinions but my own. I have not yet heard how the book is liked.

I am much obliged to you and Stevenson and the others who intended coming to the rescue, and my present object is to say so. I beg you will thank the gentlemen concerned, and accept of my sincere thanks in your own presence. I shall be in Albany in a few days, on my way south. Until then adieu – Very truly yours,

J. Fenimore Cooper

D.D. Barnard, Esquire

By the time that award was settled, the Pellet libel suit had brought Cooper another $400 verdict, and he had filed numerous libel suits, many that he litigated on his own behalf and won.

The Cooper libel trials and related legal proceedings both darkened his own final years and placed him in a bad light with the American public. Beyond that, the issues raised by the disposition of these cases influenced the move to redefine the libel law in New York State so that suits like Cooper’s would have little success in the future.

Image for reference only; not included