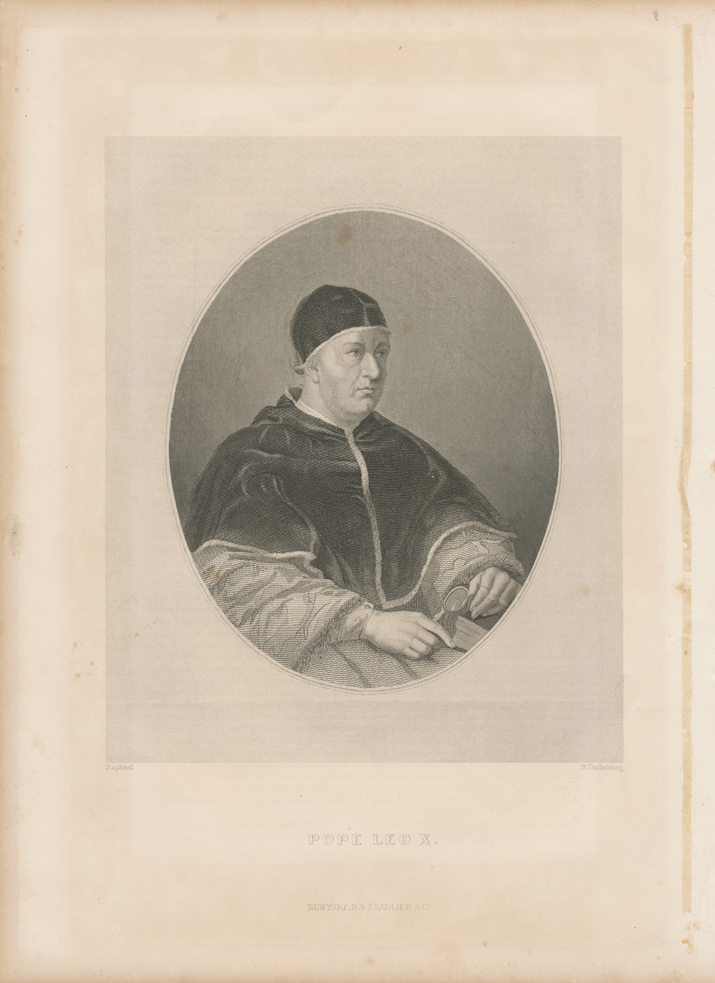

Pope Leo X de' Medici

Pope Leo X de' Medici

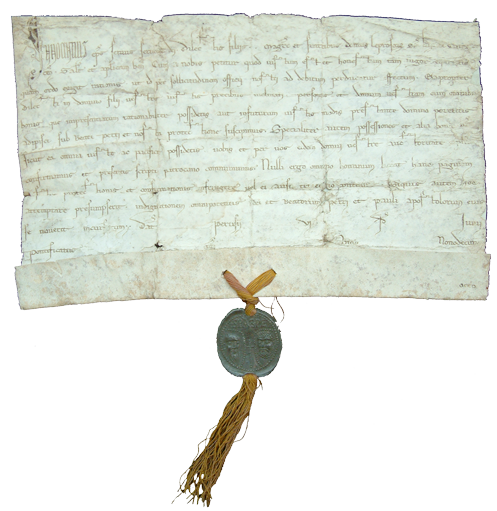

Papal Bulla Medallion - 1517

Papal Bulla struck in 1517 for Pope Leo X de’ Medici, with a scarce though generous tuft of yellow silk cord still attached at each end, indicating this bulla had been appended to a document of some importance. Approximately 1.5″ (40mm) diameter, 3/8″ (5mm) thick, weighing 1.5 ounces (45g). Also included is a vintage engraving of Pope Leo X taken from an 1868 book, perfect for a framed presentation.

A papal bull is a particular type of letter or charter issued by a Pope of the Roman Catholic Church. Papal bulls were originally issued by the pope for many kinds of communication of a public nature, but by the thirteenth century, papal bulls were only used for the most formal or solemn of occasions. These documents came in various grades of importance, signified by aspects of the formality of the document, by the elaboration of the calligraphy, and by the means of attaching the seals. It is named after the lead seal (bulla) that was appended to the end in order to authenticate it, the most distinctive characteristic of a bull.

Example of a Papal Bull from Pope Innocent III in 1216, with bulla attached.

Most bullae were usually made of lead, but on very solemn occasions they were made of gold. The obverse depicted the founders of the Church of Rome, the apostles Peter and Paul, identified by the letters Sanctus PAulus and Sanctus PEtrus. The name of the issuing pope appeared on the reverse side. The most important documents had the seals attached with red or yellow silk cords, while documents of lesser significance had them attached with hemp cords. Visual symbolism was of paramount importance for papal documents.

At nearly 500 years old, this bulla is in remarkably fine condition, though the notations of the saints have worn away through the centuries. A clearer representation of Leo’s bullae with saints’ initials intact appears in 1929’s Manuel de Diplomatique Française et Pontificale (Paris: Auguste Picard) by A. de Boüard:

Pope Leo X (Giovanni Romolo de’ Medici) (born 1475-died 1521; reigned 1513-1521). Second son of Lorenzo “the Magnificent” de’ Medici and Clarice Orsini, the man to become Pope Leo was trained in the humanities and received a doctorate in canon law from the University of Pisa in 1492. He was earlier appointed cardinal, in 1489 at the age of 14, the last non-priest to assume the papacy.

Elected pope by the younger cardinals in 1513, Leo X took his responsibilities seriously. At religious ceremonies he presided with dignity and devotion. To preserve orthodoxy he threatened Martin Luther with penalties should he fail to recant forty-one propositions (Exsurge Domine, 1520); he then excommunicated the recalcitrant friar in 1521. To Henry VIII he assigned also in 1521 the title “Defender of the Faith” for writing against Luther. While he actively supported the observant movement in religious orders, he failed to effect a serious reform of the Roman Curia—because it would have reduced his revenues.

Pope Leo X de’ Medici in his official portrait as painted by Raphael in 1518-1519;

Cardinals Giulio de’ Medici and Luigi de’ Medici were added in later.

Leo was a lavish patron of arts and letters. While negotiating with kings and emperors for the future of Europe, Leo found time for the pleasures he loved. Artists, writers, and musicians came to Rome from all over Italy at his request. He employed Michelangelo to carve the Medici tombs in Florence, and in Rome he commissioned Raphael to work on the frescoes in the papal apartments and loggia, design the tapestries in the Sistine Chapel, paint his papal portrait, and supervise the construction of the new St. Peter’s Basilica and excavations of Roman archeological sites. He set up a Greek printing press in Rome and encouraged the Jewish community in the city to begin their own printing operation. Church positions were found for writers, poets, and translators, some of the more favored of whom he made bishops. Leo himself was a master of classical Latin and delighted in giving impromptu speeches in the style of Cicero. He commissioned plays and had them performed before his court. As a connoisseur of the arts, he was unequaled in Europe. While he was pope, Rome became the cultural center of the West.

Leo particularly liked to hunt and did so in a grand style. The Pope and his entourage beginning a chase was as much a show for the Roman people as a sport for the papal court. He would frequently attend Mass before he set out and would sometimes offer the Mass himself. But religion, although valuable, never interfered with what he considered the important demands of his position. When the papal finances began to show the strain of Leo’s extravagant expenses, he unhesitatingly made use of his religious powers for added income. He demanded a fee from all new bishops and cardinals and authorized the selling of indulgences throughout Germany to obtain money for a grand rebuilding of Saint Peter’s Basilica, Rome’s most important church.

A polished Renaissance prince, Leo was also a devious politician and a nepotist. His aim was to keep Italy and his own Florence free from foreign domination and to advance his family outside Florence. When he discovered a plot in his own palace to poison him, Leo had one cardinal executed and another put in prison. To neutralize the power of the remaining officials, he created 31 new cardinals, all members of his own family or people he could otherwise trust. One of his last political moves was to form another alliance with Emperor Charles V and King Henry VIII of England to drive the French out of northern Italy again. His first cousin Giulio de’ Medici (1478-1534), whom he appointed archbishop of Florence, cardinal, and vice-chancellor of the church, was his closest adviser and would eventually succeed him as Clement VII (reigned 1523-1534). By his lavish expenditures on culture and warfare, and despite his efforts to raise new revenues by the sale of venal offices, dispensations, and indulgences, Leo X left the papacy deeply in debt at the time of his sudden death from malaria.